A widely publicized DOD report identified 4 bases with the toxins

In March, 2018 the DOD released a report, Addressing Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluotooctanoic Acid (PFOA) that identified contaminated water in and around military bases across the country as a result of using aqueous film-forming foam in routine fire-fighting exercises.

The report included four installations in Maryland that had dangerously high levels of the carcinogens in the groundwater:

- Annapolis 70,000 ppt.

- Chesapeake Beach 241,110 ppt.

- Fort Meade 87,000 ppt.

- White Oak 1,365 ppt.

The military has led the public to believe that releases of these toxins were limited to the four installations in Maryland. When Ms. Maureen Sullivan, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Environment, testified on the PFAS crisis in front of the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works on March 28, 2019, both of my Senators from Maryland (Van Hollen and Cardin) said that the PFAS contamination was confined to “at least” four bases in the state. They didn’t ask where additional exposure may be occuring. My senators failed to subject Sullivan to serious questioning. Sen. Cardin said the source of the contamination in Maryland is not well understood.

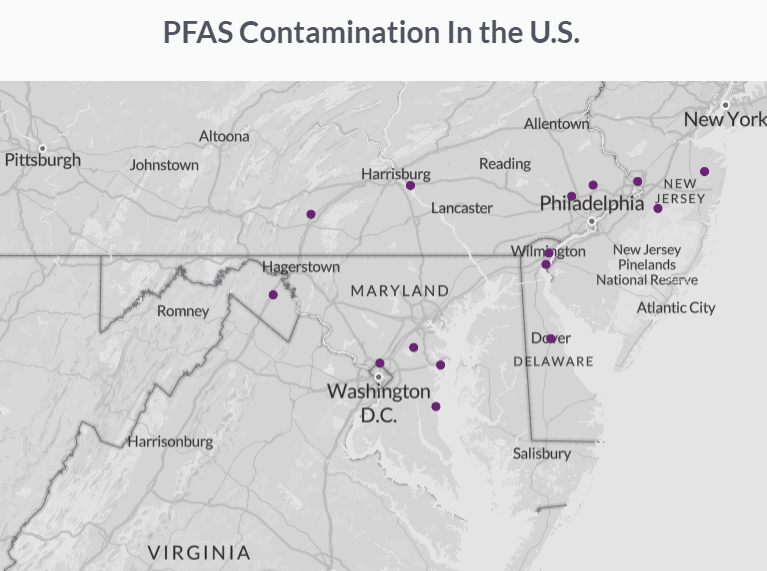

Meanwhile, a widely distributed interactive map published by the Environmental Working Group shows PFAS Contamination by the military limited to the same four bases.

A closer examination of military records and press reports reveals there are at least eleven additional bases that have a record of PFAS contamination.

Below is an examination of the four bases that are known to have releases of PFAS, followed by reports on the 8 bases here:

- Aberdeen Proving Ground, Harford County, MD

- Bainbridge Naval Training Center, Port Deposit, Maryland

- Bethesda Naval Support Activity, Bethesda, MD

- Indian Head Naval Surface Warfare Center, Indian Head, MD

- Joint Base Andrews, Camp Springs, MD

- Patuxent River Naval Air Station, Lexington Park, MD

- Solomons Island Navy Recreation Center, Solomons, MD

- Webster Field Annex, St. Inigoes, MD

Three additional bases appear in the report, “Aqueous Film Forming Foam Report to Congress Nov 3, 2017 – DoD Installations with a Known or Suspected Release of PFOS/PFOA. No other information is known on these bases regarding PFAS contamination.

- Air Force-Air National Guard, Martin State

- Naval Surface Warfare Center Carderock,

- Walter Reed National Military Medical Center

The March, 2018 DOD report identifies 36 military installations across the country that were found to have drinking water containing PFAS above the EPA’s Lifetime Health Advisory (LHA) of 70 ppt. The military also tested 2,445 off-base public and private drinking water systems and found that 564 systems tested above the EPA LHA level for PFOS and PFOA.

FFOS and PFOA are two of the deadliest Per and Poly Fluoroalkyl Substances, or PFAS. There are more than 5,000 varieties of PFAS today, and they’re all considered to be toxic.

The military has poisoned groundwater across Maryland with these chemicals. The poisons are allowed to leach into the ground to contaminate neighboring communities which use groundwater in their wells and municipal water systems.

The health effects of exposure to these chemicals include frequent miscarriages and other severe pregnancy complications. They contaminate human breast milk and sicken breast-feeding babies. PFAS contribute to liver damage, kidney disease, high cholesterol, an increased risk of thyroid disease, testicular cancer, and micro-penis.

There are currently no legally enforceable federal or Maryland standards for PFAS releases. Instead, the EPA has established an LHA of 70 ppt. An LHA (Lifetime Health Advisory) is the concentration of a chemical in drinking water that is not expected to cause any adverse noncarcinogenic effects for a lifetime of exposure. The LHA is based on exposure of a 70-kg adult consuming 2 liters of water per day.

In the absence of EPA enforcement, several states (although not Maryland) have established maximum contaminant levels for PFAS. New Jersey, for instance, recently implemented the nation’s toughest mandatory drinking and groundwater standards of 10 ppt for PFAS and 10 ppt for PFOA, although the limits do not apply to the military. (Joint Base McGuire Dix-Lakehurst in New Jersey was found to have 1,688 ppt of PFOA in its drinking water, 160 times higher than the new limit.)

Environmental groups in New Jersey had called for a limit of 5 ppt for each chemical. Philippe Grandjean and colleagues at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health say PFAS exposure of 1 ppt in drinking water is detrimental to human health.

The military has only been publicizing part of the story regarding the lethal contamination in the Old Line State.

Annapolis – Former Naval Weapons Facility:

Annapolis was one of four military installations that were included in the well-publicized March, 2018 DOD report, Addressing Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) – Maureen Sullivan Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (Environment, Safety & Occupational Health)

https://partner-mco-archive.s3.amazonaws.com/client_files/1524589484.pdf

In 54 out of 68 wells tested by the military in Annapolis, concentrations of PFAS were found to exceed 70 ppt and some were recorded 70,000 ppt., a thousand times greater than the EPA lifetime limit levels. According to the Arundel Patriot, the location of the AFFF releases is in Annapolis near the Woods Landing development in the St. Margaret’s area which was a former Naval Weapons Facility. The wells tested drew from the Patapsco Aquifer.

Both the City of Annapolis and the Naval Academy pump drinking water from the same Patapsco Aquifer, although the city does not test for these contaminants. They don’t have to. There are no federal or state laws that require them to do so.

The Director of Public Works for the City of Annapolis, who oversees drinking water and water treatment for the city, was approached last year by The Arundel Patriot, one of the few media outlets in the state covering the story. Annapolis city officials had not received notification of the DoD report showing 70,000 ppt of PFAS in the groundwater and were not familiar with the contaminants.

Carbon filter and ion exchange technology are the best ways to begin to filter out PFAS before drinking water is presented to a vulnerable human population. The City of Annapolis water treatment process does not use either of these methods because of the exorbitant cost. Besides, PFOS/PFOA are not regulated by the EPA, so costly carbon filter or ion exchange technology was not implemented when the water treatment facility was upgraded in 2017.

Chesapeake Beach Naval Research Laboratory Chesapeake Bay Detachment

The Chesapeake Bay facility in Chesapeake Beach was one of four military installations that were included in the well-publicized March, 2018 DOD report, Addressing Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) – Maureen Sullivan Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (Environment, Safety & Occupational Health)

https://partner-mco-archive.s3.amazonaws.com/client_files/1524589484.pdf

The Navy has poisoned the groundwater in Chesapeake Beach with 241,110 ppt. of PFAS. In 2017, the Navy initiated an investigation of PFAS in on-base groundwater and found that the carcinogens are present as a result of routine use of AFFF. According to the Navy, “Since PFAS are in the shallow groundwater, there is the potential for these substances to also be present in private drinking water wells in the designated areas because of their proximity and location relative to the Naval Research Laboratory – Chesapeake Bay Detachment Fire Testing Area where the Navy performs testing of these extinguishing agents.”

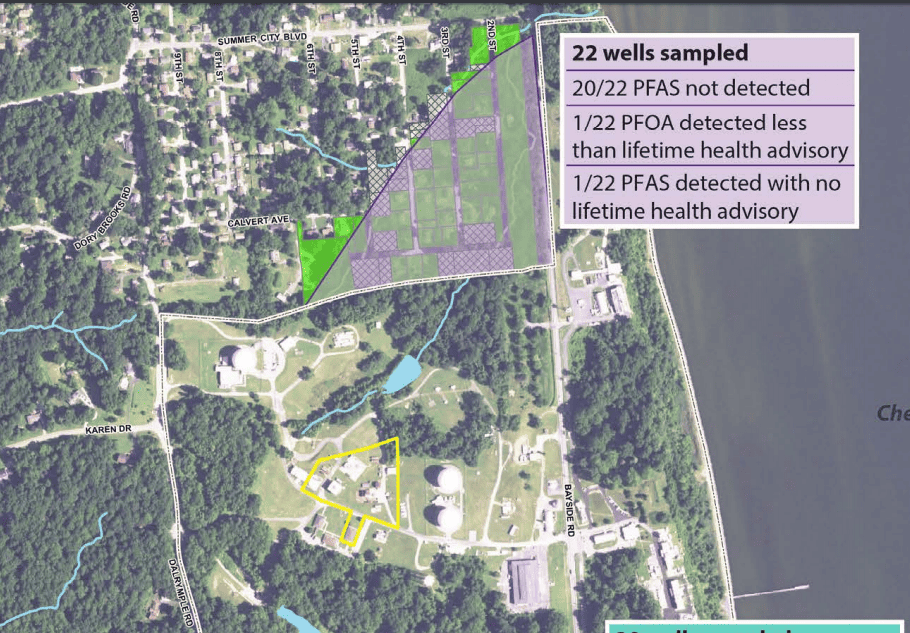

The Navy says it identified property parcels suspected to have drinking water wells within the designated sampling areas.

Several homes on 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th streets were tested. The area within the yellow boundary (above) is used for fire-training purposes and the groundwater at that location has been found to contain dangerously high levels of carcinogens. The Navy did not test the wells of homes along Karen Drive and Dalrymple Road that are just a few hundred feet from the fire pit.

One well the Navy tested on the numbered streets was found to have PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic acid) at less than 70 ppt. Although we don’t know the level of PFOA found in the well in Chesapeake Beach, the state of New Jersey does not allow more than 10 ppt of PFOA in its drinking water.

The Navy also says one well was found to have a type of PFAS that does not have an LHA established by the EPA. There are more than 5,000 PFAS chemicals and they are all deemed to be toxic, however, the EPA has only established LHA’s on two of the chemicals in the class, PFOS and PFOA.

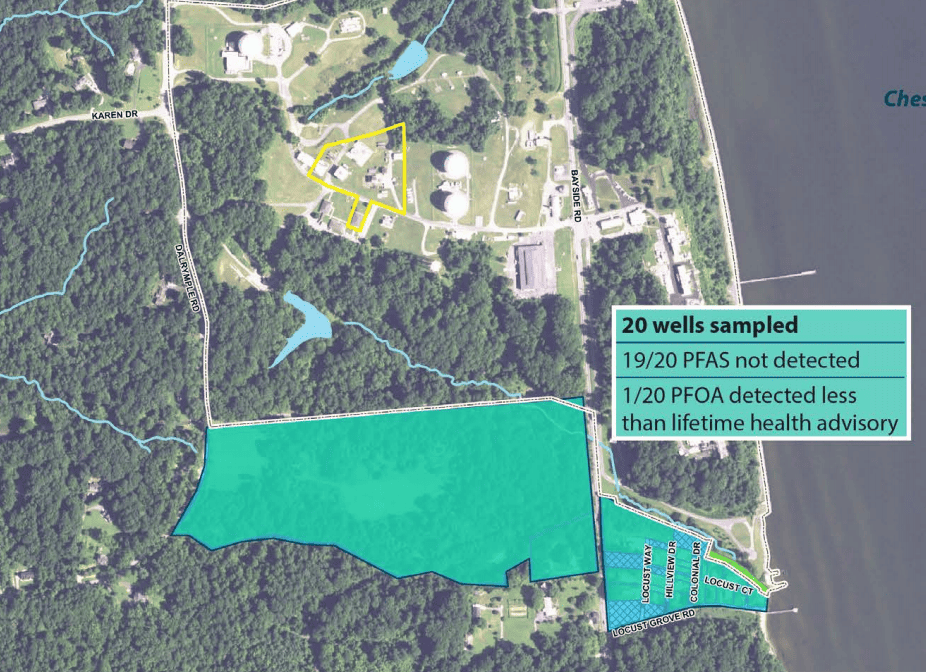

The following aerial photo shows the southern area of Chesapeake Beach where the Navy collected well samples.

The Navy tested a handful of wells off Locust Grove Rd. south of the base. The homes are four times further away from the release of AFFF than the homes near Karen Drive and Dalrymple Road. One home in the Locust Grove neighborhood was found to have PFOA present, although we don’t know the levels of the carcinogens.

The Navy says there is “no legal requirement to conduct drinking water testing. It is a voluntary measure because water quality for our off‐base neighbors is a priority for the Navy.” More responsible EPA regulations would ban the substances outright and require testing of private wells as far as the cancer-causing plume may spread, which in some cases may be several miles.

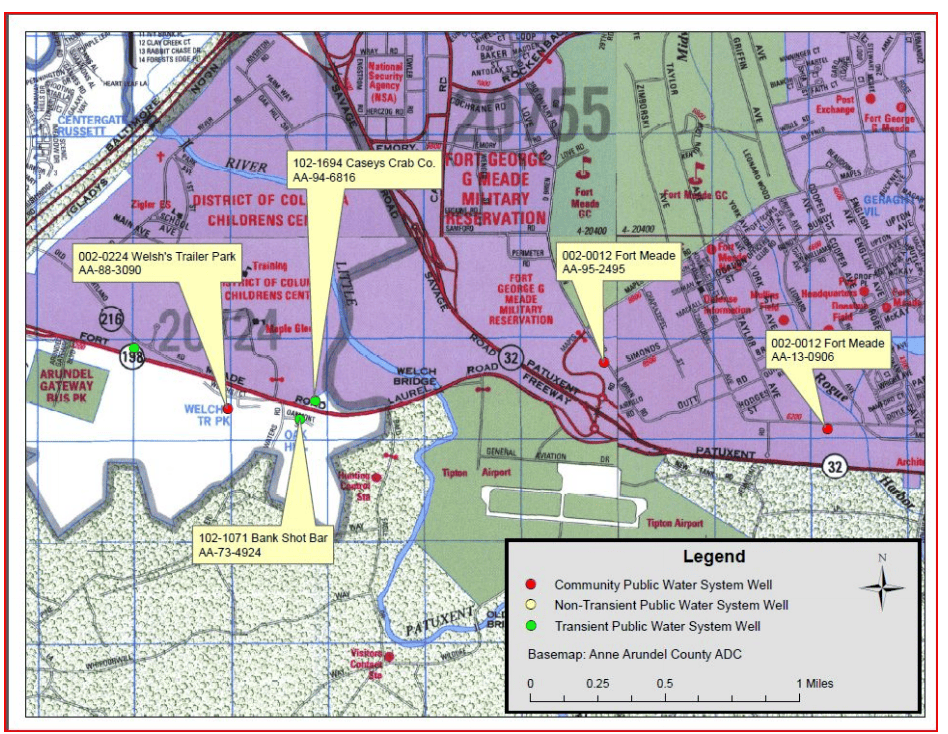

Fort George G. Meade (Army)

Fort Meade was one of four military installations that were included in the well-publicized March, 2018 DOD report, Addressing Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) – Maureen Sullivan Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (Environment, Safety & Occupational Health)

https://partner-mco-archive.s3.amazonaws.com/client_files/1524589484.pdf

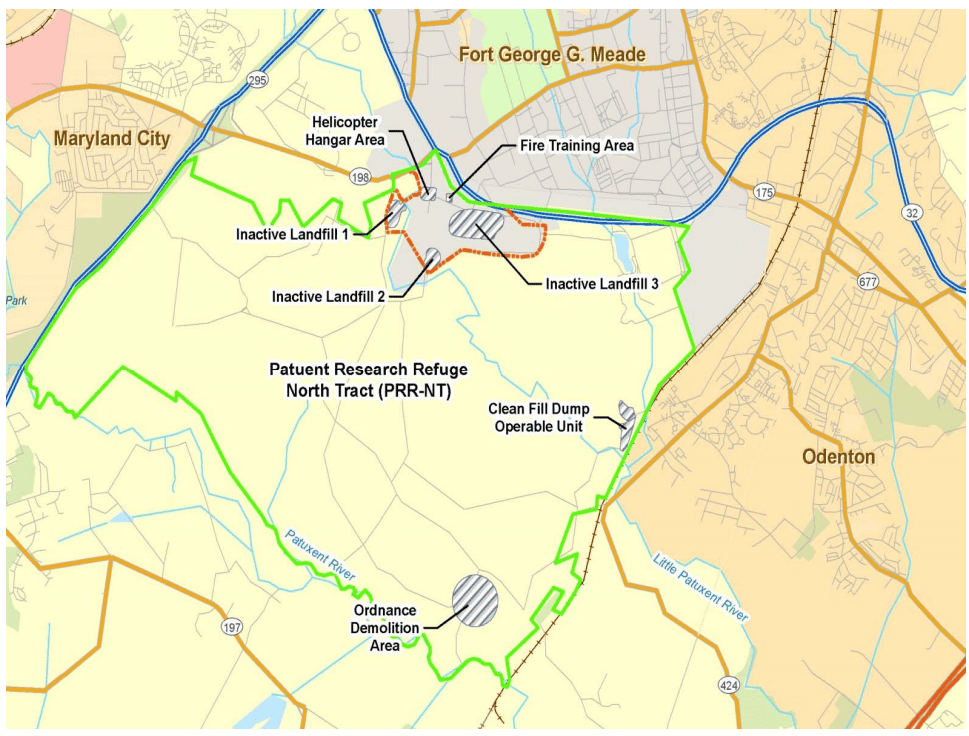

Groundwater monitoring wells in close proximity to a former DoD fire-training area where AFFF was routinely used show groundwater contaminated with 87,000 ppt. PFAS is believed to be leaching into the Lower Patuxent River.

According to a Fort Meade Fact Sheet in January, 2018, two commercially owned drinking wells are within 0.5 miles of the routine AFFF releases. The commercial owners are Bank Shot Grill and Casey’s Crab Company. The Army says the wells were not sampled because they are hydraulically separated from the contamination since shallow groundwater discharges into the Little Patuxent River and deeper aquifer groundwater flow is to the southeast. It’s the same rationale used at Patuxent River Naval Air Station in deciding not to test private wells near the deadly foam releases.

The Patuxent River watershed is comprised 908 square miles and is the longest river entirely within Maryland.

See The Arundel Patriot for its excellent reporting on the toxic contamination.

PFAS releases initially contaminate shallow groundwater while there is debate over the likelihood of PFAS contaminating the deeper aquifer.

In 2014 the Anne Arundel County Department of Health conducted an investigation of groundwater contamination within the Patapsco Aquifer beyond the Ft. Meade boundary. Although the county did not test for PFAS, they identified three groundwater contaminant plumes within the Lower Patapsco Aquifer that extends beneath the town of Odenton. The identified contaminants were trichloroethene (TCE), tetrachloroethene (PCE) and carbon tetrachloroethene (CC14). The toxins are widely used at Fort Meade.

White Oak Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division Detachment, Silver Spring, MD

White Oak was one of four military installations that were included in the well-publicized March, 2018 DOD report, Addressing Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) – Maureen Sullivan Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (Environment, Safety & Occupational Health)

16 wells were tested at White Oak and 8 were found to have PFAS in concentrations above the EPA’s LHA of 70 ppt. That’s all we know. The property is situated along New Hampshire Avenue in densely populated Silver Spring.

Aberdeen Proving Ground, Harford County, MD

In 2012 Aberdeen Proving Ground testing showed the presence of “perflourinated compounds” in two of the seven Harford County wells. “Perfluorinated compounds” is a term still used to refer to the group of toxic chemicals that includes PFOA and PFOS and other per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs).

Aberdeen, located on the Chesapeake Bay in Harford County, is one of the most contaminated Army installations in world. The DOD allocated $120 million for environmental restoration activities during FY 2018 alone.

Bainbridge Naval Training Center Port Deposit, Maryland

Bainbridge Naval Training Center, at Port Deposit, Maryland, is located on the bluffs of the northeast bank of the Susquehanna River. The base is included on a list compiled by the Navy of installations showing bases with known or suspected releases of PFAS. The Navy has identified the fire training area to be the source of the AFFF releases.

In 1990, the Fire Training Area was included in the Installation Restoration Program (IRP), which was established by the U.S. Department of Defense to identify and remediate contamination caused by historical disposal activities and other operations at military bases. The Fire Training Area was utilized to train recruits in fire-fighting techniques by spraying buildings with oil and igniting them.

Bethesda Naval Support Activity

Bethesda is included in a database compiled by the Department of Defense Environmental Restoration Program (DERP) showing Sites with Potential PFC/PFAS Contamination. The former lab disposal area has been designated as an area of concern. Bethesda is responsible for base operational support for its major tenant, the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

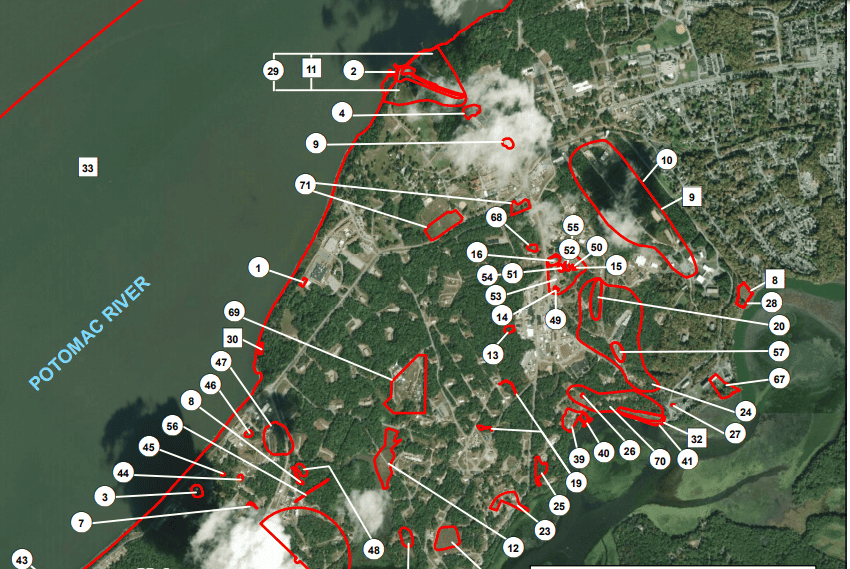

Indian Head Naval Surface Warfare Center

Indian Head Naval Surface Warfare Center on the Potomac River in Charles County recently added Site 71 as an area of environmental concern.

The site has five separate areas where PFAS-laced fire-fighting foams are believed to have been used on the base. The Navy refers to “the potential use of foam containing PFAS in fire training exercises.” Throughout the military’s literature, use of the carcinogenic foam is referred to as the “potential use” or “suspected use.”

Two of the locations are at the Main Area along S. Patterson Road behind the firehouse and near the intersection of W. Farnum Road and S. Dashiell Road. The remaining three are at Stump Neck Annex in the contractor lot along Archer Ave, the helicopter pad near Building 2174, and the field behind Building 1SN. The Navy has scheduled a preliminary assessment for the site and a SAP (Sampling and Analysis Plan) is expected to be submitted for review sometime this year.

The DOD allocated $186 million for various environmental cleanup measures during FY 2018.

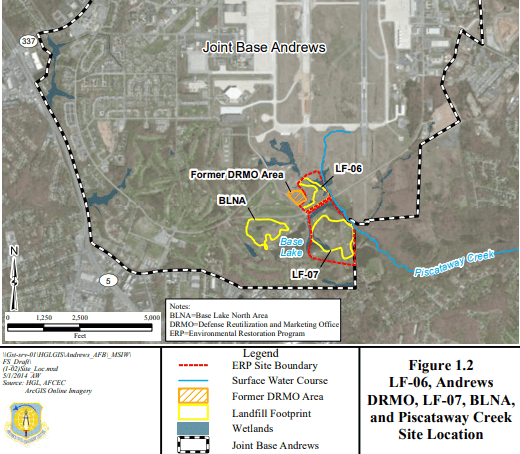

Joint Base Andrews, Camp Springs, MD

The following excerpts are taken from: FINAL FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR LF-06, (Landfill 06) ANDREWS DRMO, Defense Reutilization and Marketing Office PISCATAWAY CREEK (AOC-33), LF-07, (Landfill 7) AND BASE LAKE NORTH AREA (BLNA) (D-2) March, 2019 – Prepared by: HydroGeoLogic, Inc.

The Air Force is involved in an internal squabble on how to handle PFAS contamination at Andrews. See the back and forth between the EPA and the Air Force.

On September 4, 2018 The EPA wrote to the Air Force regarding PFAS releases at Joint Base Andrews. “Lastly, according to Air Force guidance and historical use of AFFF, the Air Force recommends that landfills be evaluated for the release of PFCs into the environment. EPA agrees. LF06, LF07 and BLNA should all be evaluated for AFFF (PFCs) or per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) releases.

Air Force Response (Feb. 26, 2019) Comment noted.

EPA Comment: Lastly, according to Stephen TerMaath, Ph.D., P.E., Base Realignment & Closure Program, (BRAC) Management, AFCEC, Air Force Civil Engineer Center, (AFCEC) participation in Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program, (SERDP) and Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP) Webinar Series Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs): Analytical and Characterization Frontiers, January 28, 2016, the Air Force recommends sampling for PFCs at landfills.

Air Force Response (Feb. 26, 2019): PFOS/PFOA at JB Andrews will be addressed in the future under a separate effort. Any PFOS/PFOA comment given by the BRAC manager for AFCEC made at a SERDP conference does not constitute Air Force policy. Air Force policy and overall DoD policy regarding PFOS/PFOA continues to evolve and change in light of changing state and federal regulatory standards.

Note: The Air Force is thumbing its nose at the EPA while coming across to the public as divided in its commitment to protecting human health.

EPA Comment: Sampling for PFCs are necessary and needs to be documented in the FS (Feasibility Study), the executive summary, site history as well as referenced in the alternatives including the preferred alternative. Maintaining existing monitoring wells is appropriate because they could be used for future PFC sampling and analyses.

Air Force Response: PFC sampling is not a part of the remedy. However, a statement that the presence of PFOS/PFOA at Piscataway Creek will be addressed under a separate effort appears in the Executive Summary, the description of the nontime critical removal action in Section 1.5, and the recommendations in Section 4.4.

Note: It’s early June, 2019 and there’s nothing new on the releases of PFAS into Piscataway Creek. There’s nothing new pertaining to PFAS at Andrews and that’s the way the Air Force would like to keep things if its track record across the country is any indication.

Patuxent River Naval Air Station, Lexington Park, MD

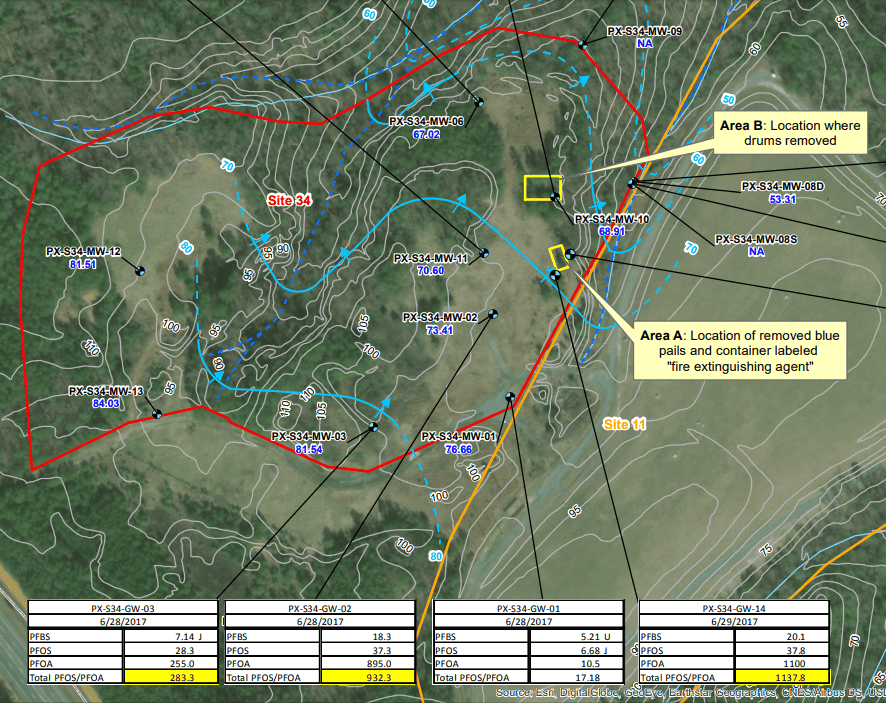

The Navy has contaminated the groundwater at the Patuxent River Naval Air Station with 1,137.8 ppt of (PFAS). See Figure 4. The contamination was not reported on the DOD’s March, 2018 report on PFAS, Addressing Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluotooctanoic Acid (PFOA).

Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) containing PFAS has been extensively used in hangars and at multiple locations on the base in fire training exercises. Much of the contamination is associated with Site 41 – The Old Firefighting Burn Pad, and Site 34 – The Drum Disposal Area. Site 34 is located a quarter mile from Rt. 235 near the southwest corner of the base. The area adjacent to the base is populated with many homes served by groundwater wells.

The Navy’s evaluation of the sites on base that have been identified as having known or suspected releases of PFAS was limited to existing Environmental Restoration (ER) sites. These areas were found by the Navy “to have no complete exposure pathway to a potential drinking water source, hence, no off-base drinking water sampling was initiated.”

The Navy reviewed 24 production wells across the station with well depths ranging from 284 to 900 feet. These wells are all within the Piney Point-Nanjemoy aquifer or the deeper Aquia aquifer and not within the surficial aquifer which ranges from 10-100 feet deep. The Navy says the hydrogeologic setting does not indicate a transport pathway into the deeper Piney Point-Nanjemoy and Aquia aquifers from the surficial aquifer because of the thickness of the clays and silts in the ground.

Case closed? Can it be definitively stated that this zone is under a fully confining and laterally continuous unit? Wouldn’t relatively inexpensive testing of adjacent privately-owned wells be a prudent course of action? Like Fort Meade and Chesapeake Beach, private wells within a half-mile of known and routine releases of PFAS have not been tested.

The Navy says the contaminated streams that originate on the base stay within the station boundaries until draining directly or indirectly into the Patuxent River or the Chesapeake Bay. Both Fort Meade and Pax River NAS contaminate the Patuxent River with PFAS.

In 2010 the US Geological Survey collaborated with the University of Maryland and sampled the Patuxent River specifically for PFOS (Perfluorooctane Sulfonate) and found concentrations of 22 ppt. The Patuxent River is two times more polluted than what New Jersey allows in its groundwater.

Are the crabs and fish in the Patuxent safe to eat? Does this level of contamination pose a threat to aquatic life and the humans who consume seafood?

Based on the recorded history of releases and gathered information on the base, nine high priority sites were identified that were likely impacted by PFAS from the release of AFFF. The Navy says the environmental impact at these sites are estimated to be minimal for multiple reasons: the majority of the releases occurred over 25 years ago, diluted AFFF foam was released instead of AFFF concentrate, and releases were single incidents over short periods of time.

Despite the Navy’s assertions, the length of time since the release of these carcinogens is immaterial because PFAS never breaks down in nature. It is why they are called “the forever chemicals.” It explains how PFAS is currently found in the groundwater at England AFB in Louisiana at concentrations of 10,9000,000 ppt. That base closed 27 years ago. The concentration of the contaminants and the frequency of release are also inconsequential. PFAS in microscopic amounts is dangerous to all living organisms. Harvard health professionals say 1 ppt. of PFAS in drinking water is potentially harmful.

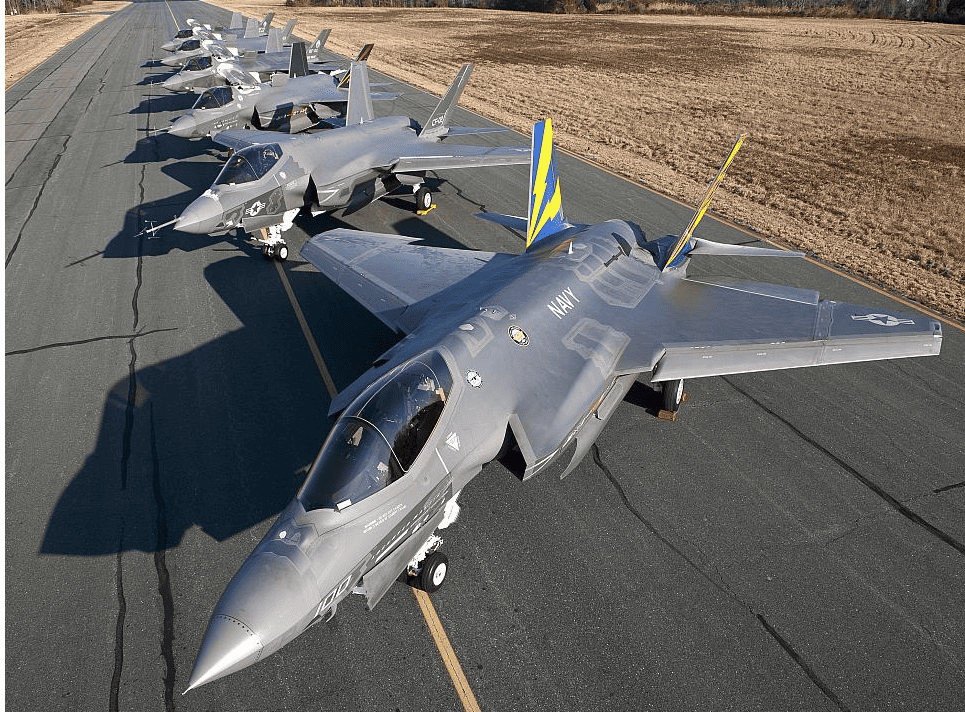

For years, pipes carried expired jet fuel, diesel fuel or waste oil to an old fuselage set in a 200 x 200-ft pit on a concrete pad at the Patuxent River base. Massive fires were routinely ignited and doused by the PFAS-laced AFFF. The carcinogens were allowed to leach into the ground and discharge to surrounding stormwater ditches and sewer drains. The Navy has known of the serious environmental and health impacts of PFAS since 1974.

Hangar 2133 at Patuxent River is equipped with an AFFF cannon fire suppression system supplied by 4,000-gallons of PFAS foam. Multiple inadvertent releases have occurred in the hangar. These releases occurred in November 2002, June 2005, and April 2010. During one of these incidents (date unknown), the cannon system for the entire hangar was activated inadvertently. The Navy says the quantities of AFFF concentrate or foam for these releases are unknown. A similar mishap at Eglin Air Force Base took two minutes to create 3 feet of cancer-causing foam to cover a two-acre hangar.

The 2010 release of AFFF at Patuxent River resulted in a notable quantity of foam being sent to the sanitary sewer via the bypass valve of the oil/water separator, effectively “foaming” the METCOM wastewater treatment plant. Nearly 500 gallons of AFFF was released in mid-2000s. The foam reportedly went to an oil- water separator which leads to METCOM sewer drains. Another release in 2011 sent 150 gallons of AFF down the drain to METCOM.

All sewage from the Patuxent River Naval Air Station is pumped to the Marlay – Taylor Water Reclamation Facility. The potentially carcinogenic wastewater sludge produced is disposed by land application at various locations throughout St. Mary’s County.

Solomons Island Navy Recreation Center

The Solomons Island Navy Recreation Center is included on a list compiled by the Navy showing bases with known or suspected releases of PFAS. All the branches of the military refer to “suspected” or “potential” releases of the cancer-causing substances, even though they’re aware of the past use of AFFF using these chemicals.

Unexploded ordnance (UXO), discarded munitions, munitions constituents (MC), and other munitions and explosives of concern (MEC) are found at the Recreation Center. The Navy says these sites do not present contamination concerns.

Petroleum storage tanks spill contaminated substances at the recreation center. The spills are documented and stored in a spill database.

The Solomons Recreation Center is classified as a Large Quantity Generator (LQG) of hazardous wastes. PCBs were originally used at the Solomons Rec. Center in transformers located throughout the installation. Due to what they consider to be the low risk of human exposure, the Navy has implemented no environmental restrictions or land use controls associated with PCBs. Asbestos-Containing Material remains present in many buildings and lead-based paint covers the inside and outside walls in many buildings. Due to the age of many buildings and the lack of clean-up efforts, it is suspected that buildings built before 1978 contain Lead-based paint.

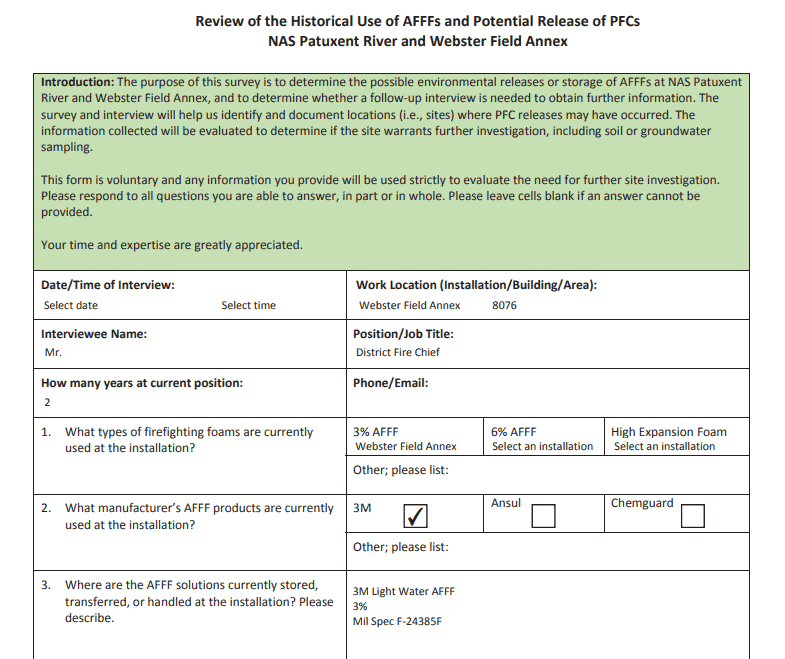

Webster Field Annex, St. Inigoes, Maryland

Three fire trucks currently carry AFFF at Webster Field. They are parked in Fire Station 3 Building 8073. The fire station houses 245 gallons of the chemicals while the trucks carry 3M 3% AFFF. The trucks are tested daily for spray patterns to ensure the equipment is working properly. The spray tests are in front of the fire station. The trucks are supplied with AFF in 5-gallon buckets. The vehicles are cleaned/decontaminated using soap and water. The base is located on a thin sandy peninsula, bordered by St. Inigoes Creek and the St. Mary’s River.

AFFF used by the U. S. military must meet the requirements set forth in Military Specification MIL-F-24385F, which is under the control of the Naval Sea Systems Command. The “mil-spec” calls for the use of carcinogenic PFAS.

Outside the United States many countries have switched to non-fluorinated foams and/or foams that do not contain PFAS.

Click to Subscribe to the Civilian Exposure Newsletter for Latest News & Updates Today!

4 comments

[…] by the military at eight bases, although it has not publicly acknowledged additional contamination at numerous other installations in the state. Alarmingly, there have been no advisories issued regarding the consumption of seafood […]

[…] PFAS are a serious risk in Maryland. A report found that at least 15 military bases have been contaminated by PFAS chemicals, for example. Meanwhile, PFAS chemicals have also been […]

[…] finalizing a statewide survey for sites where PFAS have been used. They should start by looking at these 15 military bases in the state. We ought to remain skeptical and judge them by their deeds rather than their […]

[…] are another 8 bases that are believed to have used PFAS that the MDE omitted in its […]